2.2 Gang Activity and Youth Violence: Guidance

This procedure was updated on 23/03/21 and is currently uptodate.

Contents

- Introduction(Jump to)

- Local Profile(Jump to)

- Definition of a gang(Jump to)

- Principles(Jump to)

- Serious Youth Violence(Jump to)

- Environmental Factors(Jump to)

- Gang Involvement(Jump to)

- Formation of gangs(Jump to)

- Weapons(Jump to)

- 'Stop and search' powers(Jump to)

- Alcohol and drugs(Jump to)

- Gang associated sexual violence and exploitation(Jump to)

- Use of the internet and mobile phones(Jump to)

- Sign and symptoms of gang involvement(Jump to)

- Children at risk of becoming serious violent offenders(Jump to)

- Looked after children(Jump to)

- Education establishments(Jump to)

- Health(Jump to)

- House and social landlords(Jump to)

- Community groups / voluntary agencies and faith groups(Jump to)

- Response(Jump to)

- Parental engagement(Jump to)

- Osman Warnings(Jump to)

- Risk of harm to professionals(Jump to)

- Information sharing and intelligence(Jump to)

- Appendix(Jump to)

- Related Policies, Procedures, and Guidance(Jump to)

- Bibliography(Jump to)

- Footnotes(Jump to)

Introduction

| 2.2.1 | This guidance is for frontline staff and managers working in both voluntary and statutory agencies. It will also be helpful for individuals in Buckinghamshire’s local communities and community groups, who also have a role in identifying and safeguarding children who are vulnerable to, or at risk from, involvement in or targeting from:

|

| 2.2.2 | This guidance supplements the Home Office guidance ‘Safeguarding Children and Young People who may be affected by gang activity’ (2010) and should be read in conjunction with the Buckinghamshire Safeguarding Children Partnership Core Procedures. |

Local Profile

| 2.2.3 | Information from Thames Valley Police in 2016 reveals there are a small number of gangs in existence across Buckinghamshire, with the majority based in the Wycombe area. Historically, there has been a higher number of gangs across the area, however, due to police enforcement and intervention programmes provided by the Gangs Multi Agency Partnership (GMAP), this has been reduced. |

| 2.2.4 | Gangs tend to consist of young people (who can be as young as 10 years old) and are geographically specific. Within Buckinghamshire, most gang activity is located within High Wycombe, with 3–4 gangs. Local gangs tend to consist of young people drawn from a range of ethnic backgrounds, mostly male. While they may start as social entities, giving group members a shared sense of identity, they can become involved in causing anti-social behaviour, with the majority of members continuing on to more serious criminal activity, particularly drug supply. |

Definition of a gang

| 2.2.5 | Defining what constitutes a ‘gang’ can be difficult, partly because its characteristics are known to change over time and locality. Being part of a friendship group is a normal part of growing up and it can be common for groups of children and young people to gather together in public places to socialise. These groups should be distinguished from ‘gangs’ for whom crime and violence are a core part of their identity – although ‘delinquent peer groups’ can also lead to increased anti-social behaviour and youth offending. |

| 2.2.6 | Although some group gathering can lead to increased anti-social behaviour and youth offending, these activities should not be confused with the serious and organised violence of a gang. |

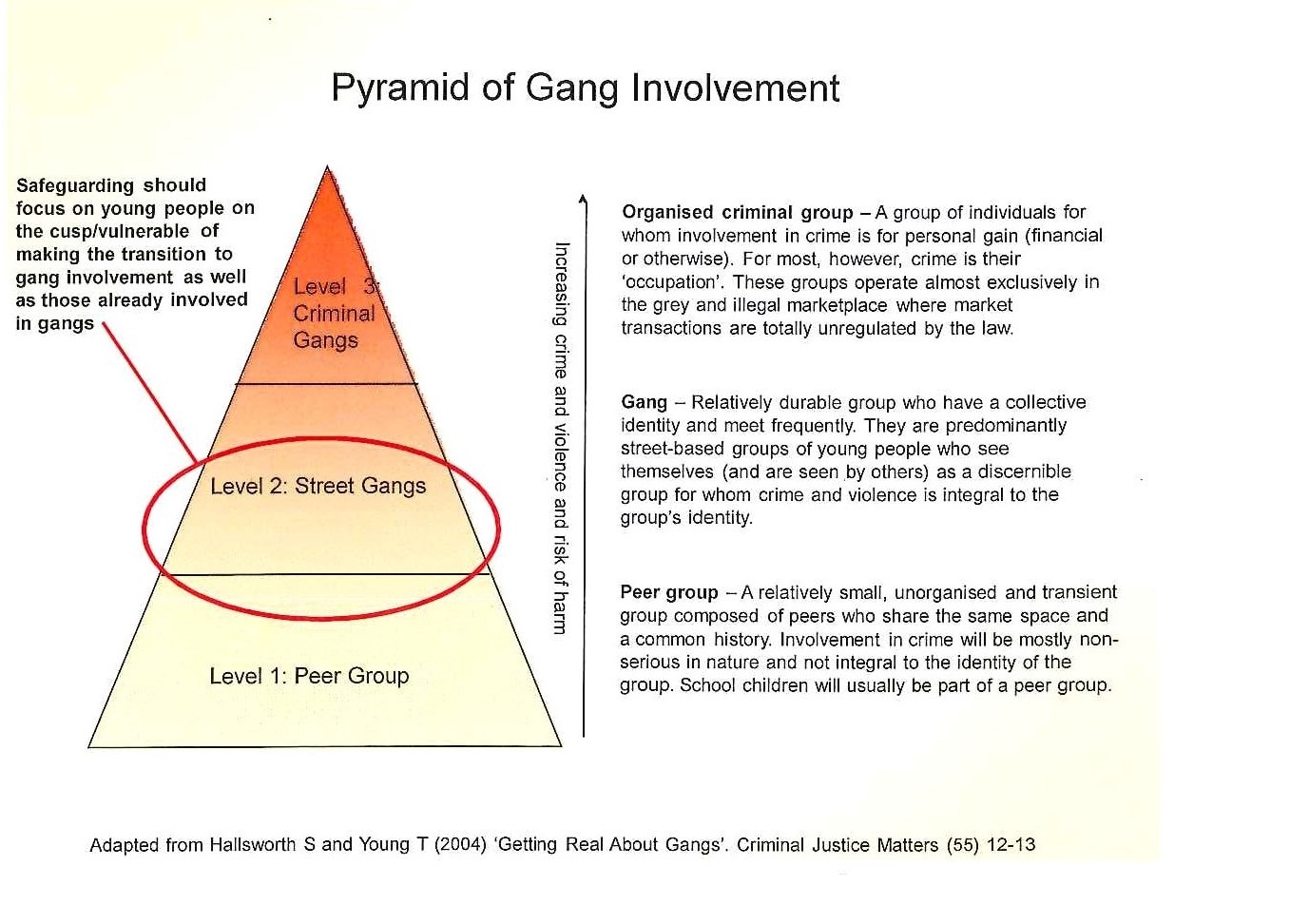

| 2.2.7 | Hallsworth and Young[1], and Gordon[2] set out the following definitions:

|

| 2.2.8 | Gordon also suggests that definitions may need to be highly specific to particular areas or neighbourhoods if they are to be useful. Furthermore, professionals should not seek to apply this or any other definition of a gang too rigorously; if a child or others think s/he is involved with, or affected by, ‘a gang’, then a professional should act accordingly in assessing the risk to the child as both a potential perpetrator and a victim. |

| 2.2.9 | The diagram below sets out a tiered approach to defining gangs. This guidance is focused on those young people on the periphery of becoming involved with street gangs and those young people already involved.

|

Principles

| 2.2.10 | The following principles should be adopted by all agencies in relation to identifying and responding to children (and unborn children) who are at risk of, or are being, affected by gang activity and/or serious youth violence:

|

Serious Youth Violence

| 2.2.11 | The majority of children do not become violent, and those that do tend not to become violent in a short space of time. For the latter, their behaviour represents many years of (increasingly) anti-social and aggressive acts, with aggressive habits learned early in life often the foundation for later behaviour. Where a child succeeds at low-level anti-social acts, such as verbal abuse and bullying, violating rules and being disruptive, he/she may feel emboldened to perpetrate increased violence. However, any public discussion around serious youth violence should contain messages that reassure the public and build confidence, i.e. that the vast majority of young people contribute positively towards society. Serious youth violence is committed by a small minority (less than 2%) of young people. |

Environmental Factors

| 2.2.12 | Several factors are important contributors in potentially increasing an individual child’s propensity to act violently:

|

| 2.2.13 | Exposure to media images of violence increases a child’s fear of becoming a victim of violence, with a resultant increase in self-protective behaviours and a mistrust of others.[3] It desensitises the child to violence, resulting in increased callousness towards violence directed at others and a decreased likelihood to take action on behalf of the victim when violence occurs. It also increases a child’s willingness to become involved with violence or exposing themselves to violence. |

| 2.2.14 | Where children’s viewing is not regulated, they can readily access graphic violence, often with sexual content, through TV, the internet, on DVD and through playing age-inappropriate games. |

Gang Involvement

Recognition and respect | |

| 2.2.15 |

|

Group behaviour | |

| 2.2.16 |

|

Formation of gangs

Community and family circumstances | |

| 2.2.17 |

|

Reluctant or naive gang members | |

| 2.2.18 |

|

Weapons

| 2.2.19 | Fear and a need for self-protection is a key motivation for children to carry weapons – carrying a weapon affords a child a feeling of power. Neighbourhoods with high levels of deprivation and social exclusion generally have the highest rates of gun and knife crime. |

| 2.2.20 | Many children do not seek active involvement in gun crime and if they do use a gun are horrified by what they have done. |

| 2.2.21 | Knives and other weapons are far more prevalent than firearms, especially in the case of children. The Offending, Crime and Justice Survey highlights that:

Carrying weapons increases the risk of serious injury or death while defending oneself or fighting, and the risk multiplies in group situations. |

Knives: What is and is not legal? | |

| 2.2.22 |

|

'Stop and search' powers

| 2.2.23 | Police officers have the right to search any person where there is a reasonable high level of suspicion of an offence, including carrying an offensive weapon. A reasonable or high level of suspicion is required before search powers can be evoked. |

| 2.2.24 | Professionals working with children who may have reason to be fearful in their neighbourhood or school/further education, college etc should be alert to the possibility that a child may carry a weapon. |

Alcohol and drugs

| 2.2.25 | The use of alcohol and illegal drugs can play a major role in violence involving young people. Children and young people’s use of drugs can bring them into contact with adults who are involved in organised crime, supplying drugs. The drugs business tends to attract career criminals who regulate the market through often extreme violence or the threat of violence. |

| 2.2.26 | Children often carry drugs (or weapons and stolen property) for the older gang members, so that they can be stopped and searched with impunity. Children are also known to serve jail terms for older gang members. |

Gang associated sexual violence and exploitation

| 2.2.27 | Sexual violence incorporates any behaviour that is perceived to be of a sexual nature, which is unwanted or takes place without consent or understanding. It is a wider concept than that of child sexual exploitation. |

| 2.2.28 | Child sexual exploitation is: The sexual exploitation of children and young people under 18 involves exploitative situations, contexts and relationships where young people (or a third person or persons) receive ‘something’ (e.g. food, accommodation, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, affection, gifts, money) as a result of performing, and/or others performing on them, sexual activities… Child sexual exploitation can occur through use of technology without the child’s immediate recognition, for example the persuasion to post sexual images on the internet/mobile phones with no immediate payment or gain. In all cases, those exploiting the child/young person have power over them by virtue of their age, gender, intellect, physical strength and/or economic or other resources. Violence, coercion and intimidation are common, involvement in exploitative relationships being characterised in the main by the child or young person's limited availability of choice resulting from their social/economic and/or emotional vulnerability. |

| 2.2.29 | A common feature of child sexual exploitation is that the child or young person does not recognise the coercive nature of the relationship and does not see themselves as a victim of exploitation. Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse, but what differentiates it from other forms of abuse is the concept of exchange – the fact that the young person or the person abusing them receives something in return for the abusive act. |

| 2.2.30 | The majority of gang members are male, although there are a number of female gangs. Members or female gang Girls are more likely to be subservient in predominantly male gangs, often being used to carry or stash weapons and drugs. |

| 2.2.31 | In some localities female members of gangs are often on the receiving end of violence and extortion, and their relationships with other gang members tend to be abusive. Initiation rituals are sometimes based on sexual violence, with female members of their own gang or, more often, on the female members of a rival gang. |

| 2.2.32 | Very few incidents of sexual violence by gang members are reported, with girls being extremely reluctant to identify their attackers, and often intimidated and threatened not to talk. |

| 2.2.33 | An American study of gang behaviour concluded that group sexual assault (and other types of assault) mainly occurs in an environment where group behaviour and acceptance is important to the young men involved. An individual who might otherwise not have perpetrated a sexual assault, may do so in situations where the presence of others acting in a similar fashion diminishes the individual’s feeling of responsibility for the harmful consequences of his own behaviour. |

| 2.2.34 | Sexual exploitation may be evident in gangs in the following forms:

|

| 2.2.35 | Gang members often groom girls at school and encourage/coerce them to recruit other girls through school/social networks. There is also anecdotal evidence that younger girls (some as young as 10 or 12) are increasingly being targeted, and these girls are often much less able to resist the gang culture or manipulation by males in the group. The girls often do not identify their attackers as gang members and tend to think of them as boyfriends. They may also be connected through family or other networks. |

| 2.2.36 | Girls are often groomed using drugs and alcohol, which act as dis-inhibitors and also create dependency. |

| 2.2.37 | Female relatives of gang members could also be at particular risk of either being under pressure to have sex with gang members or of being the victim of sexual violence by another gang. Siblings are particularly at risk, but other members of the wider family may also be exploited in this way. |

| 2.2.38 | Please also refer to the BSCP guidance on child sexual exploitation:

|

Use of the internet and mobile phones

| 2.2.39 | The internet has increasingly become a key recruitment tool to help gangs expand, both in terms of territory and the number of members in each gang. Young members typically use mobile phones to conduct drug transactions and arrange meetings. |

| 2.2.40 | Gang leaders actively reach out through popular online services to create a new generation of gang members. They describe gang life as glamorous and seductive. Recruiters tell of a life of power, leisure and wealth, and instant gratification, as well as a ‘family’ and sense of belonging that many young people may desperately want. |

| 2.2.41 | Feedback from young gang members in London is consistent with this: “I don’t see it as being in a gang; it’s more like being in a family.” (Roxy, age 15, member of 2 London gangs) |

| 2.2.42 | For the most part, gangs use popular social media sites: Facebook, YouTube, SnapChat, Instagram and Twitter. The videos and photos posted may just be about their lives, but frequently include documentation of crimes they want to brag about. The sites are also used to convey threats and to intimidate. The threats exchanged online create a new cause for offline violence as gang members settle disagreements that started online. |

Sign and symptoms of gang involvement

| 2.2.43 | Children as young as seven years old can be involved in a gang. Professionals who have contact with children should be competent in identifying the signs and symptoms which, particularly when clustered together, can raise concerns that a child may be either reluctantly or willingly involved with a gang. |

| 2.2.44 | Indicators include:

|

| 2.2.45 | The framework in the Appendix provides greater detail around high, medium and low level risk factors and indicators. |

| 2.2.46 | It seems that the more heavily gang-involved a child is, the less likely she/he is to talk about it. However, if a child does talk about gang involvement, professionals should always take what the child tells them seriously. |

Children at risk of becoming serious violent offenders

| 2.2.47 | Professionals who have contact with children should be competent in identifying the combinations of signs and symptoms which can place children at risk of becoming serious and violent offenders. Additional indicators for this include:

|

Looked after children

| 2.2.48 | Looked After children are particularly vulnerable due to their low self-esteem, low resilience, attachment issues and the fact that they are often isolated from family and friends. There are risks specific to different types of placements, such as secure units, children’s homes, foster homes, or living in semi-independent accommodation. |

| 2.2.49 | Professionals in all agencies who have contact with Looked After children should be alert to their increased vulnerability to being gang-involved, targeted by gangs or adversely affected by gang activity. These children could potentially be at risk of harm from serious youth violence. |

| 2.2.50 | When looked after children are known to be involved with, or affected by, gangs, professionals need to take into account gang territory and gang membership when planning placements for Looked After children, to avoid placing a child in a situation which exposes him/her to serious youth violence. |

| 2.2.51 | At reviews, the Independent Reviewing Officer should recommend that a team manager convenes a multi-agency professionals or network meeting if there are concerns that a child may be vulnerable to gang involvement and/or serious youth violence. There needs to be clear lines of accountability for any Looked After child who is vulnerable to, or affected by, gang activities and/or serious youth violence. |

| 2.2.52 | All children’s homes should have access to a local professional with specialist knowledge in relation to gangs and serious youth violence, or a gangs and serious youth violence team. |

| 2.2.53 | Looked After Children cases will be managed in line with the Children’s Social Care Procedures for Looked After Children. |

Education establishments

| 2.2.54 | All education establishments can be affected by gang activity. |

| 2.2.55 | Some primary schools report conflict between self-styled gang members. From time to time, gang-affiliated youngsters from secondary schools are summoned to a primary school by their younger brothers and sisters as reinforcements in the aftermath of an ‘inter-gang’ playground dispute. |

| 2.2.56 | In some areas, further education colleges can be where gang activity and/or serious youth violence can gain momentum because, unlike schools, gangs are more likely to view further education colleges ‘as belonging’ to particular gangs. This ownership can give rise to incidents of serious youth violence on the premises and create an atmosphere of fear and intimidation. |

| 2.2.57 | In recent UK studies, almost two thirds of 23 active gang members interviewed had been permanently excluded from school, with the exclusions often resulting from gang involved and gang-affected children attempting to bring weapons onto school premises. |

| 2.2.58 | These studies confirmed that children involved in anti-social behaviour and gangs tend to see academic striving as ‘uncool’ and, as a result, educational failure can come to be accepted as the norm amongst them. |

Health

| 2.2.59 | Health professionals, in particular GPs and Accident and Emergency staff, may become concerned about a child’s involvement in serious youth violence due to injuries or wounds, particularly those caused by sharp instruments or knives. |

| 2.2.60 | Health professionals may also come into contact with girls who they suspect may have been sexually exploited or abused, perhaps through Genito-Urinary Medicine (GUM) clinics, sexual health services and GPs. Professionals should be alert to a child’s likely reluctance and fear of discussing this. |

House and social landlords

| 2.2.61 | Through their housing management function, social landlords are well placed to identify risk and to make a strong contribution to delivering positive outcomes across the range of preventive, enforcement and/or resettlement strategies. |

| 2.2.62 | Incidences of gang activity and/or serious youth violence are high-level concerns for social landlords and their residents in the neighbourhoods in which they manage properties. |

| 2.2.63 | There is also a key role for the hostel/supported housing sector who may be accommodating the young people themselves. This includes 16/17-year-old ‘children in need’ who are accommodated under Section 20 of the Children Act, and whose circumstances may make them particularly vulnerable to exploitation by gangs. These types of services are uniquely placed to pick up on risk factors and also to work with young people attempting to break away from gang activity. |

Community groups / voluntary agencies and faith groups

| 2.2.64 | Community groups/voluntary agencies can be well placed to know the profile and location of local gang activity, and potential or actual serious youth violence, through their community links and the work they do to support children and their families. In addition, community workers and professionals from voluntary agencies can be best placed to reach children who are at risk of harm from their peers. |

| 2.2.65 | Gang-related ‘territorialism’ and serious youth violence can make community, voluntary or youth work difficult in any local area. In these circumstances, safe outreach work rather than building-based activities can be an effective way forward. |

Response

Identifying a child at risk from gang activity and/or serious youth violence | |

| 2.2.66 |

Providing early help

Assessing levels of need and referral to children’s social care

|

Parental engagement

| 2.2.67 | Wherever possible, professionals in all agencies should involve parents as early as possible in cases where there are concerns that a child may be affected by gang activity and serious youth violence. The child and his/her parents should be invited to any multi-agency meeting to discuss the concerns. |

| 2.2.68 | The exception to this is where professionals have concerns that to involve parents would risk further harm to a child or undermine a criminal investigation. If the parents are not invited, the reason should be recorded in the minutes of the meeting, together with a written undertaking that a named person informs them of the outcome of the meeting. |

| 2.2.69 | Where there are difficulties in engaging with parents, staff should consider alternative ways of achieving co-operation, including the use of community organisations and/or community leaders to facilitate the work with parents/family. |

Osman Warnings

| 2.2.70 | A warning regarding threat to life, or an Osman Warning, is so named after the Osman v United Kingdom case (1998) which placed a positive obligation on the authorities to take preventive measures to protect an individual whose life is at risk from the criminal acts of another individual. In the context of gangs, this may occur as a result of gang rivalry or because of an incident occurring within a young person’s own gang (for example threatening to leave or refusing to commit an act of violence). |

| 2.2.71 | If the police give an Osman Warning to a young person they should inform Children’s Social Care and consider whether:

|

Risk of harm to professionals

| 2.2.72 | Professionals should be aware of any potential threats to their safety during interaction with a child and should make a decision on the suitability of a home visit. It may be more appropriate to interview the child and/or parents and carers in a neutral setting. |

| 2.2.73 | Agencies may need to consider putting in place protocols for managing risk of harm to professionals/staff in this context. All professionals should have access to competent and consistent risk management advice. It may be appropriate for security measures to be taken such as ensuring professionals can access panic alarms and mobile phones, as well as conflict resolution training for frontline staff. |

Information sharing and intelligence

| 2.2.74 | Staff in all agencies need to be confident and competent in sharing information appropriately to safeguard children who are at risk of harm through gang activity and/or serious youth violence. |

| 2.2.75 | All agencies are empowered to share information without permission for the purpose of crime prevention under Section 115 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, although obtaining consent is good practice. |

| 2.2.76 | In considering whether to share information, professionals should also refer to the BSCP Information Sharing Code of Practice and the Government’s information sharing advice for safeguarding practitioners. |

| 2.2.77 | Professionals should seek advice from their safeguarding lead if they are in any doubt as to whether or not information should be shared. |

| 2.2.78 | Police officers who interact daily with young people are often best placed to recognise signs that a young person may either already be a gang member or is at most risk of being recruited into a gang. A responsibility rests with all to ensure that intelligence around those affected by gangs is accurately recorded and then shared with partner agencies, in order that appropriate strategies can be implemented. |

Appendix

Related Policies, Procedures, and Guidance

Bibliography

- London Safeguarding Board. Safeguarding children affected by gang activity and/or serious youth violence. 2010

- Victim Support, Hoodie or Goodie? The Link Between Violent Victimisation and Youth Offending: A Research Report. 2007

- Victim support publications and research reports

- Goode, E and Ben-Yehuda, N. Moral Panic: The construction of deviance. 2009 Sociology Index, Sociology Books.

- Thompson, C et a Representing Gangs in the News: media constructions of criminal gangs. 2000. Sociological Spectrum 20. 409-432

- USA: Surgeon General’s Commission Report (1972), National Institute of Mental Health Ten Year Follow-up (1982) & Report of the American Psychological Association’s Committee on Media in Society (1992)

- The Centre for Social Justice. Girls and Gangs. 2014.

- Home Office. Injunctions to prevent gang-related violence and drug dealing. 2016.

- HM Government. Injunctions to prevent gang-related violence and gang-related drug dealing. 2016.

- Early Intervention Foundation. Preventing gang and youth violence. 2015

Footnotes

[1] Hallsworth, S and Young, T. Getting Real About Gangs, Criminal Justice Matters 2004 (55) 12-13

[2] Gordon, R. Criminal Business Organisations, Street Gangs and “Wanna Be” Groups: A Vancouver perspective. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 2000. vol. 42

[3] Joint Statement on the Impact of Entertainment Violence on Children, Congressional Public Health Summit, July 26, 2000