3.8 Self-Harm: Guidance

This procedure was updated on 23/06/22 and is currently uptodate.

Contents

- Introduction(Jump to)

- Definition(Jump to)

- Causes and triggers(Jump to)

- Warning Signs(Jump to)

- Self-harming Behaviour(Jump to)

- Coping Strategies(Jump to)

- The urge to escape difficulties(Jump to)

- How to help(Jump to)

- Health response when you seek medical support for a child(Jump to)

- Longer-term support(Jump to)

- Understanding and preventing self-harm(Jump to)

- Confidentiality(Jump to)

- Contagion, Multiple and Copycat behaviours(Jump to)

- Impact on people working with young people(Jump to)

- Further information for parents / carers, children and young people(Jump to)

- Related Policies, Procedures, and Guidance(Jump to)

- RESOURCES to support professionals working with children who self-harm.(Jump to)

Introduction

| 3.8.1 | These guidelines provide information for people working with children and young people on how to support people up to the age of 18 who harm themselves, and how to access appropriate services where needed. |

| 3.8.2 | This document can be read alongside the following additional guidelines: |

Definition

| 3.8.3 | Self-harm is any behaviour, initiated by the individual, which directly results in physical harm to that individual. Physical harm will be considered to include bruising, laceration, bleeding, bone fractures and breakages and other tissue damage (Murphy and Wilson, 1985). |

| 3.8.4 | The Mental Health Foundation define the difference between deliberate self-harm and suicide:

|

| 3.8.5 | Some people who self-harm have a strong desire to kill themselves. However, there are other factors which motivate people to self-harm, including a desire to escape an unbearable situation or intolerable emotional pain; to reduce tension; to express hostility; to induce guilt or to increase caring from others. Even if the intent to die is not high, self-harming behaviour may express a powerful sense of despair and needs to be taken seriously. Moreover, some people who do not intend to kill themselves may do so, because they do not realise the seriousness of the method they have chosen to self-harm or because they do not get help in time. |

| 3.8.6 | HBSC England findings (2014) Main heading (publishing.service.gov.uk) suggests that over the past decade rates of self-harm have been increasing among adolescents . HBSC findings indicated that the likelihood of self-harming varied by social economic status and structure of households, the incidence of self-harming is associated with lower family affluence. |

| 3.8.7 | The majority of people who self-reported self-harm are aged between 11 and 25 years, however, self-harming behaviours are most likely to occur between the ages of 12 and 15 years. The HBSC Study (2014) Main heading (publishing.service.gov.uk) identified prevalence rates at 22% for 15 year olds in England. Nearly three times as many girls as boys reported that they had self-harmed, 11% of boys compared to 32% of girls. The majority of those young people who were self-harming reported engaging in self-harm once a month or more. |

| 3.8.8 | There were 181 hospital admissions as a result of self-harm per 100,000 children and young people aged 0 to 17 years in 2017/18. This is higher than the rate in 2013/14 (177 admissions per 100,000) Self_harm_and_mental_health.ods (live.com) |

| 3.8.9 | In the vast majority of cases, self-harm remains a secretive behaviour that can go on for a long time without being discovered. Many children and young people may struggle to express their feelings and will need a supportive response to assist them to explore their feelings and behaviour and the possible outcomes for them. |

Causes and triggers

| 3.8.10 | Any assessment of self-harm behaviours should begin with a consideration of the possible triggers of such behaviour. The causes/triggers of self-harm behaviours can relate to internal factors and/or external factors. When considering triggers it is important to not only look at the immediate triggers, but recognise that past triggers or an accumulation of many triggers over time may well result in the young person showing self-harming behaviour. |

| 3.8.11 | The following risk factors, particularly in combination, may make a young person vulnerable to self-harm: Individual factors

Family factors

Social factors

|

| 3.8.12 | People of any age, gender, ethnicity or background may find themselves using self-harm as a coping mechanism for many different reasons. However, professionals should be aware that for some children and young people protected characteristics (for example disability, being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender or coming from a black or minority ethnic background) may be a factor in self-harm. The increased bullying, hate crime and isolation experienced by children and young people in these groups is likely to play a part. For example, research by Stonewall suggests that two in five (41%) of LGB school pupils have attempted or thought about taking their own life directly because of bullying and the same number say that they deliberately self-harm directly because of bullying. According to the same report, 59% of trans youth said they had deliberately hurt themselves, compared with 8.9% of all 16- to 24-year-olds. |

| 3.8.13 | The pressures for some groups of young people and in some specific settings may increase the risk of self-harm, for example:

|

| 3.8.14 | A number of factors may trigger the self-harm incident:

|

| 3.8.15 | A more detailed list of potential cases and triggers of self-harm for children and young people with special education needs and disabilities can be found in the document Self-Injurious Behaviour: Guidelines and resources to help support children and young people with special educational needs and disabilities who show self-injurious behaviours. |

Warning Signs

| 3.8.16 | There may be changes in the behaviour of the young person which are associated with self-harm or other serious emotional difficulties, for example:

|

| 3.8.17 | Some young people get caught up in mild repetitive self-harm such as scratching, which is often done in a peer group. In this case it may be helpful to take a low-key approach, avoiding escalation, although at the same time being vigilant for signs of more serious self-harm. |

Self-harming Behaviour

| 3.8.18 | Examples of self-harming behaviour include:

|

| 3.8.19 | Self-harm can be a transient behaviour in young people that is triggered by particular stresses and resolves fairly quickly, or it may be part of a longer-term pattern of behaviour that is associated with more serious emotional/psychiatric difficulty. Where there are a number of underlying risk factors, the risk of further self-harm is greater. |

| 3.8.20 | Once self-harm (particularly cutting) is established, it can be difficult to stop. Self-harm can have a number of functions for the young person and it becomes a way of coping, including:

|

| 3.8.21 | When a person inflicts pain upon himself or herself, the body responds by producing endorphins, a natural pain reliever that gives temporary relief or a feeling of peace. The addictive nature of this feeling can make self-harm difficult to stop. |

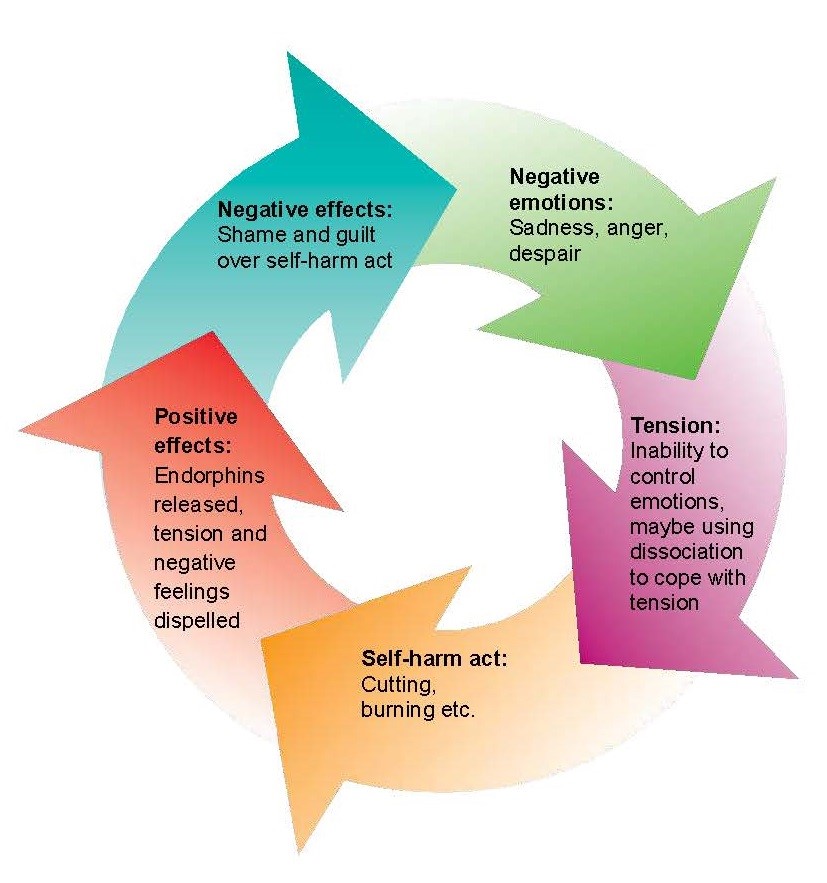

| 3.8.22 | Young people who self-harm still feel pain, but some say the physical pain is easier to stand than the emotional/mental pain that led to the self-harm initially. The cycle of self-harm / cutting |

Coping Strategies

| 3.8.23 | Using support networks It is helpful to identify supportive individuals and networks in a young person’s life and how to get in touch with them. Examples are friends, family, school teacher, counsellor. Knowing how to access a crisis line is also important. |

| 3.8.24 | Distraction activities Replacing the cutting or other self-harm with other safer activities can be a positive way of coping with the tension. What works depends on the reasons behind the self-harm. Activities that involve the emotions intensely can be helpful. Examples of distraction activities include:

|

| 3.8.25 | Coping with distress using self-soothing Self-soothing techniques include:

|

| 3.8.26 | Discharging unpleasant emotions in other ways Sometimes it can be helpful to find other ways of discharging emotion which is less harmful than self-harm, including:

|

| 3.8.27 | In the longer term, a young person may need to develop ways of understanding and dealing with the underlying emotions and beliefs. Regular counselling/therapy may be helpful. Support from family members or carers is likely to be an important part of this. It may also help if the young person joins a group activity such as a youth club, a keep fit class or a school-based club that will provide opportunities for them to develop friendships and feel better about themselves. Learning stress-management techniques, ways to keep safe and how to relax may also be useful. |

The urge to escape difficulties

| 3.8.28 | For some young people, self-harm may express the strong desire to escape from a conflict or unhappiness at home, and to live elsewhere. Injuring oneself can achieve a temporary respite if it entails a hospital admission or a short break at the home of a friend or relative. The young person may request admission to foster care or a residential home and parents may doubt their ability to cope at this stage. Entering care often carries with it many long-term disadvantages and increased vulnerability for the young person. It is acknowledged that for some young people, being looked after is the best way forward but in most cases it is preferable to try to support the young person and family members in finding a resolution to their difficulties rather than to separate them further. |

| 3.8.29 | For those who are already in care, self-harm may still be an expression of a desire to escape from their situation, for example, leaving the home. As before, it is important to support the young person, understand the nature of their difficulties and help them to find a way of resolving them. |

| 3.8.30 | If you believe that a young person would be at serious risk of abuse in returning home or in remaining in their residential setting, consult their social worker for advice. |

| 3.8.31 | If a child or young person goes missing from home or from a residential setting then the BSCP procedures on missing children should be initiated. MISSING-CHILDREN-PRACTICE-GUIDANCE-FINAL.pdf (buckssafeguarding.org.uk) |

How to help

| 3.8.32 | The following steps (Helping Young People Who Self Harm: Flowchart) should be taken in the first instance when an incident of self-harm in a young person is identified. Reference should also be made to other relevant BSCP policy/guidelines as appropriate, in particular see What to do if you have a concern about a child in Buckinghamshire. Reporting a Concern - Buckinghamshire Safeguarding Children Partnership (buckssafeguarding.org.uk)

|

| 3.8.33 | The child should be included in discussions where possible based on an assessment of their age, capacity and condition at time. |

| 3.8.34 | If you are concerned that an episode of self-harm was a serious attempt by the young person to end their life, contact your local CAMHS Single Point of Access team (telephone: 01865 901 951). |

| 3.8.35 | Further strategies for schools and residential settings to help a young person who self-harms include:

|

| 3.8.36 | Schools should refer to the document 'Guidelines and resources for schools to help support children and young people who self-harm' for further information. |

Health response when you seek medical support for a child

Addition of hospita, GP, CAMHS and school health nurse.

| 3.8.37 | The role of the hospital

|

| 3.8.38 | Role of the GP

|

| 3.8.39 | Role of CAMHS CAMHS help children and young people up to 18 who are finding it hard to cope with everyday life because of difficult feelings, behaviour or relationships Depending on the risk identified for the child the timescales they will be seen in varies. See CAMHS referral information for Self-Harm. Oxford Health CAMHS Make a referral | Oxford Health CAMHS The MHST sits within the CAMHS umbrella of services and has been developed by three partner organisations, Buckinghamshire County Council, Bucks Mind and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. The service has been designed to be within schools in Buckinghamshire to provide advice, support and early help to those young people and parents who otherwise would not receive this service. |

| 3.8.40 | Role of School Health Nurses

|

Longer-term support

| 3.8.41 | It is important to understand the reasons behind the self-harm and support the young person in keeping safe. |

| 3.8.42 | Key workers/staff should work with the young person to build up self-esteem, develop problem-solving skills, and encourage strategies to cope with difficult feelings. |

| 3.8.43 | If the young person is involved with CAMHS they should be supported to attend appointments and be encouraged to make use of the support offered. |

Understanding and preventing self-harm

| 3.8.44 | It may be helpful to explore with the young person what led to the self-harm – the feelings, thoughts and behaviour involved. This can help the young person make sense of the self-harm and develop alternative ways of coping. |

| 3.8.45 | An important part of prevention of self-harm is having a supportive environment in the school or residential setting which is focused on building self esteem and encouraging healthy peer relationships. An effective anti-bullying policy and a means of identifying and supporting young people with emotional difficulties is an important aspect of this. |

Confidentiality

| 3.8.46 | Confidentiality is a key concern for young people and they need to know that it may not be possible for professionals to offer complete confidentiality. |

| 3.8.47 | If you consider that a young person is at serious risk of harming himself/herself or others, confidentiality cannot be kept. It is important not to make promises of confidentiality that you cannot keep, even though the young person may put pressure on you to do so. If this is explained at the outset of any meeting the young person can make an informed decision as to how much information they wish to divulge. |

Contagion, Multiple and Copycat behaviours

| 3.8.48 | When a young person is self-harming it is important to be vigilant in case close contacts of the individual are also self-harming. |

| 3.8.49 | Occasionally schools or residential settings may discover that a number of students in the same peer group are harming themselves. Self-harm can become an acceptable way of dealing with stress within a peer group and may increase peer identity. This can cause considerable anxiety in school staff, parents and carers, as well as in other young people. |

| 3.8.50 | It can happen that two or more young people may self-harm simultaneously. It is important that each case is looked at individually in terms of levels of risk and need in the first instance. It is of course important at a later stage to consider what it was within the group dynamic that led to this situation and how best it could be managed in the future. |

| 3.8.51 | Each individual may have different reasons for self-harming and should be given the opportunity for one-to-one support. However, it may also be helpful to discuss the matter openly with the group of young people involved. In general it is not advisable to offer regular group support for young people who self-harm. |

| 3.8.52 | Where there appears to be linked behaviour or a local pattern emerging, a multi-agency strategy meeting should be convened. |

| 3.8.53 | It is important to encourage young people to let you know if one of their group is in trouble, upset or shows signs of harming. Friends can worry about betraying confidence, so they need to know self-harm can be dangerous, and by seeking help and advice for their friend they are taking a responsible action. |

| 3.8.54 | The peer group of a young person who self-harms may value the opportunity to talk to an adult, either individually or in a small group. |

Impact on people working with young people

| 3.8.55 | People working with young people may experience a range of feelings in response to self-harm in a young person (e.g. anger, sadness, shock, disbelief, guilt, helplessness, disgust or rejection). It is important for all work colleagues to have an opportunity to seek support for their own needs and discuss the impact that self-harm has on them personally. The type and nature of the forums where these issues are discussed may vary between settings. |

| 3.8.56 | For those who are supporting young people who self-harm, it is important to be clear with each individual how often and for how long you are going to see them (i.e. the boundaries need to be clear). It can be easy to get caught up into providing too much, because of one’s own anxiety. However, the young person needs to learn to take responsibility for their self-harm. |

| 3.8.57 | If you find the self-harm upsets you, it may be helpful to be honest with the young person. You need to be clear that you can deal with your own feelings and try to avoid the young person feeling blamed. They probably already feel low in mood and have a poor self-image; your anger/upset may add to their negative feelings. However, your feelings matter too. You will need the support of your colleagues and management, if you are to listen effectively to young peoples’ difficulties. |

| 3.8.58 | In schools, young people may present with injuries to first aid or reception staff. It is important that these frontline staff are aware that an injury may be self-inflicted, and that they pass on any concerns. |

| 3.8.59 | Staff taking this role should take the opportunity to attend training days on self-harm or obtain relevant literature. Liaison with the local CAMHS may be helpful. |

Further information for parents / carers, children and young people

Coping with Self-Harm: A Guide for Parents and Carers: This freely downloadable PDF guide, which has been developed by researchers at the University of Oxford, provides information for parents and families about self-harm and its causes and effects. It is based on current research on self-harm and on the interviews with parents who children self-harmed. It contains quotes from them with advice for other parents as well as evidence-based information and links to sources of help.

Children and Young People Get Depressed Too: This leaflet from Young Minds helps distinguish between feeling depressed and when depression has become a bigger problem.

Do You Ever Feel Depressed: This leaflet from Young Minds if for children and young people who are feeling down or depressed. It talks about how normal it is for people to feel up or down at difference times, but highligts the difference between these feelings and more serious longer-term depression, which can make daily life difficult.

What Are Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: This leaflet from Young Minds is for parents or carers who child has been referred to CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services). It is also for parents and carers who want to know how to get support from CAMHS.

Worried About Self-harm?: This booklet from Young Minds aims to help those who want to find out more about self-harm and to find support for themselves or someone they know. It includes information about:

- What self harm is and why people do it.

- Thinking about stopping and getting help.

- How friends and family can help.

- Useful addresses and contact numbers.

These guidelines are based on the Self-Harm Guidelines for Staff within School and Residential Setting developed by the Oxfordshire Adolescent Self Harm Forum Steering Group. This included representatives from OBMH (now Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust), Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust, Oxfordshire County Council, Oxfordshire PCAMHS (now part of Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust), Oxfordshire Samaritans and Oxford University Centre for Suicide Research.

Related Policies, Procedures, and Guidance

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013) Self-harm Quality Standard

- NSPCC Self Harm Preventing Child Self-Harm & Keep Them Safe | NSPCC

- Mental Health Foundation (2006) Truth Hurts: Report of the National Inquiry into Self-harm among Young People

- Public Health England (2014) Intentional self-harm in adolescence: An analysis of data from the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey for England. Main heading (publishing.service.gov.uk)

- Royal College of Psychiatrists (2014) Managing self-harm in young people.

- Murphy, G and Wilson, B (1985) Self-injurious Behaviour. Kidderminster: British Institute of Mental Handicap Publications.

RESOURCES to support professionals working with children who self-harm.

1. BSCP Self-Harm. Useful contacts.

2. BSCP Helping Young People Who Self Harm: A Flow Chart.

3. BSCP Self-Harm Flow Chart for Non-Education Settings

4. BSCP Sample Letter Parent or Carer Self-Harm Guidance.

5. BSCP Flow diagram for dealing with self-harm in schools.

6. BSCP Information for Parents and Carers Self-Harm Guidance.

7. BSCP Self-Harm - Wellbeing re-Admission form

8. BSCP CAHMS Referral Information Self-Harm Guidance

9. CAMHS 16-17 year old self-referral leaflet.

10. BSCP Schools Only. Management of Health and Safety work rgulations, General Work Risk Assessment

11. BSCP Self-Ham Incident Form

12. BSCP My Safety Net Self-Harm Guidance

13. NSHN Common Misconceptions - Self-Harm.

14. NSHN What is Self-Harm - Definitions.

15. NSHN Distractions that can help.

16. Oxford University. Coping with Self-Harm. A Guide for Parents and Carers.